Memories of an encounter with the great Les Murray

By Phil Brown

![]()

Les, Kings Cross, and me

Memories of an encounter with the great Les Murray and other, far less accommodating poets.

By PHIL BROWN

We shook hands and he then led me into a small couch and I perched in a chair opposite, on the other side of a coffee table, making small talk and thanking him profusely for agreeing to publish my poem. Valerie brought in a cheese platter with a baguette and a plunger full of coffee. Les Murray sliced pieces off the baguette and carved out chunks of cheese, then reclined somewhat. I was reminded of the actor Charles Laughton, who had played the occasional Roman Em- peror in his long film career. Les was certainly emperor-like and a tad Romanesque.

Our conversation is lost in the recesses of my mind. I cannot for the life of me recall anything we spoke about. There were no smartphones to record with in those days or to get a snap of me and Les together, more's the pity. I must have been there nearly an hour when I could see Les was getting a bit restless. He had poems to write, and soon it was clear my audience was nearing an end. I asked him then to sign my copy of Lunch & Counter Lunch and he wrote in it the inscription: 'For Phil Brown, This unsteady compass needle (which at least points away from evil, I think) with warm regards from Les 7/1/1979.' I still have it and, of course, treasure it.

In parting I asked him if he was aware of any poetry readings I might attend while I was in Sin City, to which Les nodded and said he knew of one happening that very week. It was being held by the Poets Union, which met in Kings Cross. "Tell them I sent you," Les said with a wink. I wasn't quite sure what the wink signified but I would soon find out. I hadn't actually done much poetry reading at that stage. There was that poorly at- tended reading at our house when I was a student in Toowoomba, and I had read a few poems at the small-scale writers' group I at- tended in that little hall at Mermaid Beach back on the Gold Coast. Plus I had read one in Brisbane at the launch of 8 Poets 1978, my most significant publication to date.

But I was still pretty green in that department. I thought maybe this Poets Union meeting would be my na- tional debut. And Les had recommended it to me (with that wink) so I had to attend.

A couple of nights later I made my way from sedate Gordon to Kings Cross, a locale that, coincidentally, Slessor had also written about in his poem William Street which celebrated its gritty, some- what sleazy, inner-urban ambience.

While most folk regarded it as grungy and ugly, Slessor assured his readers: I find it lovely. I was propositioned several times while making my way to the reading, a nervous young poet clutching his folders on the crowded footpath. I guess I looked like someone ready to be taken advantage of.

There were the usual spruikers outside the strip clubs and the couple in front of me at one stage were stopped by the bloke framed in the doorway enticing the young woman in with this charming pitch: "Come on, luv, bring your boyfriend in - turn him on for later on."

I hurried past, eventually found the address where the Poets Union met and went upstairs.

I was greeted, if I can use that word, by Nigel Roberts, the poet who seemed to be in charge. He was a well-known figure in the Australian poetry scene, originally a Kiwi, who had made Sydney his home. When I say I was greeted by him I'm exaggerating, 'because it wasn't really what you would call a greeting. I presented, announcing that I was a poet visiting from Queens- land, and as I said this I heard someone snigger. Roberts himself, clad in a leather jacket and looking every bit the inner-city Beat poet, couldn't have been less impressed.

He looked me up and down - me in my corduroy trousers, cal- ico shirt, John Lennon glasses and little cap. I thought I looked like a poet but he didn't look so sure.

After an awkward pause - during which I got the impression he was hoping I might turn and leave - I said, nervously: "Les Murray sent me."

"Oh, yes," intoned Roberts, turning his back and walking away, "he's always palming people off on us." I was a bit thrown by this, but I must have been more resilient then than I imagined. Undeterred, I entered the establishment and sat down at a large table at the far end, away from the other poets, who looked at me as if I had just come in with dog shit on my shoe. I kind of nodded hello: nobody nodded back.

The only other poet there that I can recall from that awful even- ing was the famous Melbourne bard Pi O, who was visiting. I re- member quite clearly that he was wearing a blue singlet, a Jackie Howe (named after the famous gun shearer) or, as was commonly known back then, a wife-beater. I call it a Jackie Howe. Pi O was small, intense and interesting to listen to. The air filled with talk and laughter, people read their verses and I sat down the end of the longish table, my folders placed stra- tegically in front of me.

I flipped through the pages now and then to try and draw attention to the fact that I was there, ready to re- cite my work.

But nobody even so much as glanced in my direction. I was, to all intents and purposes, invis- ible. There were several carafes of very cheap wine on the table. Tastewise, it was noth- ing more than a kind of vinegar.

As the meeting dragged on ('drag' being the operative word), I began quaff- ing the stuff; the more they ignored me, the more I drank.

It was depressing and humiliat ing in equal measure, and eventually I realised they would not be asking me to read anything because, basically, I didn't exist. To this crowd I might as well have been Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Had the 1980 box-office hit The El- ephant Man come out a year or two earli- er, I could have hurled John Hurt's plaintive cry at the taunting crowd (mine indifferent but nonetheless taunting for all that: "I am not an animal; I am a human being; I am a man!"

Or, if I had been thinking straight, I could have had a bit of fun paraphrasing Shylock's speech from Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice: Hath not a Queenslander hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Sydney poet is? If you prick me, do I not bleed?

I wonder how that would have gone down. I didn't say any- thing, of course; just sat there drinking that cheap plonk. Inside me was a torrent of anger and shame. I wanted the earth to open up and swallow me whole while, on the other hand, I yearned to smite my tormentors.

Thinking back, I wonder how I recovered from episodes such as that. There are so many times in life when you could just go under, when you could just give up, stop trying. When you thought that you were nobody and nothing. Drunk as I was by now, I realised why Les Murray had winked at me when he suggested I attend. Was it a kind of black joke? Did he just have a really sick sense of humour, or maybe he was blooding me, pre- paring me for the slings and life as a poet (more Shakespeare, less art) and all the rejection that goes with it.

No wonder many of the poets I have known gave up along the way. I would have resigned from poetry there and then if I'd had any sense.

At the end of the meeting I stood, swaying a bit, snatched up my folders and, swearing under my breath, made for the door.

I half turned as I did so, thinking that, despite my fury and indignation, I should say good- bye. But the other poets had broken into small groups and were busy chatting so, unsurprisingly, nobody even noticed me stumble out. At least it was over. On the pave- ment outside, I was ripe for getting rolled and it's a miracle I wasn't as I staggered down William Street thinking once again of Slessor and what he had written about this place. You find this ugly, I find it lovely.

"Bugger Slessor," I muttered as I wandered off into the jangled city night.

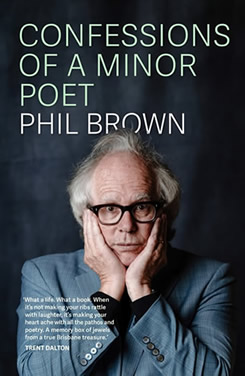

This is an edited extract from Confessions of a Minor Poet, by Phil Brown, published by Transit Lounge, $32.99

Confessions of a Minor Poet

by Phil Brown

You may also like ...

A Hong Kong Childhood

Transitlounge - 29.99

Reviews - Interviews

ANZ LitLovers LitBlog - Review

The Weekend Edition

THE LOCALS - An Interview

Brisbane News

The golden age

Cass Moriarty

What Am I Reading?

Blue Wolf Reviews - The Kowloon Kid: A Hong Kong Childhood