IN THE HEAVENLY LOBBY

Short Story by Phil Brown

My father treated the lobby of The Peninsula Hong Kong like a mixture of field office and lounge room. He felt at home at the hotel there and had been a regular since the late 1930s when the family first arrived in Hong Kong.

He was a boy when he first went there in the hotel’s early years. The hotel that has come to symbolise everything grand about the days of Empire was opened in 1928 and was built by Hong Kong tycoon Sir Ellis Kadoorie, a Sephardic Jew from the Middle East who founded the Hong Kong Hotel Company. It soon became the social hub of Kowloon and joined the ranks of other famous hotels of the east, places such as Raffles in Singapore and The Eastern and Oriental in Penang.

In a sense it was The Pen, as we called it, that really put Kowloon on the map because in Hong Kong’s early days Kowloon was regarded as a less desirable locale, even a den of iniquity at times, a place shunned by the toffs who lived on the island, mostly around Victoria Peak. The colonial administration was centred across the harbour and the colony was divided into those who lived “Hong Kong side” and those of us who lived on Kowloon.

But Kowloon became respectable and The Pen made it so. My grandfather did business at the hotel before World War Two. But when “the gin drinker’s line”, as the defenders of Hong Kong were known, capitulated and Hong Kong fell, the hotel was taken over by the occupying Japanese forces who renamed it Tao Hotel for the duration of their brutal occupation.

While they partied at the Tao Lord Roberts Brown, my Grandad Bob, was wasting way in the POW camp at Stanley on the southern shores of Hong Kong island. After the camp was liberated I’m sure my grandfather would have made for the lobby of The Pen for a stiff scotch or three.

I went there regularly with my parents throughout the 1960s and one day, in the middle of the week, I made an unexpected visit.

With a bloodied, bandaged and throbbing finger throbbing we pulled into the driveway at the front of The Pen in more of a hurry than usual.

I had been rushed to the hotel from school after an accident in the boy’s toilet. You’d think a hospital emergency room would have been more appropriate but our doctor’s rooms were on the first floor of The Pen, so I was taken straight there from Kowloon Junior School instead of to the Kowloon Hospital which was close to school.

We had been shyacking in the boy’s toilets when a friend slammed a door. The problem with that was that my hand was in the way and two fingers were squashed in the process. I let out a blood curdling yell that was obviously heard by everyone in the playground because a small crowd was gathered outside the loos when I emerged.

It was busy because it was morning break and the quadrangle was crowded with girls skipping, boys wrestling and running round.

The teacher on duty, Miss Fung, she of the enormous beehive hairdo and immaculate outfits, saw me emerge holding my hand up. I don’t think I was crying but I can’t be sure of that. My pals were standing back with innocent looks on their faces as if to say – “How did that happen?”

They quickly dispersed as Miss Fung, frowning and scolding me despite my injury, escorted me to the office. I was ushered into the headmistress’s room and was, almost immediately, overcome by the smell of strong perfume. Mrs Rosalind Versloot was a glamourous woman constantly surrounded by a cloud of Chanel. She always looked like a Hollywood starlet rather than a school teacher and she was something of a sensation with the dads.

Being in her office felt like a brush with celebrity. I was sat on a chair in her rooms, some bandages were brought and my fingers were wrapped roughly to stop the bleeding. Mrs Versloot rang my mother on the big black telephone on her desk.

“Mrs Brown,” she announced. “There has been a minor accident.”

I blanched at that because my mother was a nervous woman and I imagined her dropping to the ground, fainting dead away at the idea, while the Amah grappled with her limp body.

“Nothing too serious,” Mrs Versloot said. “Yes, yes, yes, certainly.” She turned to me.

“Your mother has called for your driver and will be here shortly to take you to the doctor.”

I nodded meekly and waited for my mother while my fingers throbbed.

It wasn’t far from Kowloon Tong to the schools my mother arrived within the half hour and whisked me out to the car where the chauffeur smiled agreeably behind the wheel as he always did. We had several drivers in our time in Hong Kong but I could never remember the name of this one.

All I can remember was that he had grey hair cut short so that his head looked like it was topped with a stiff wire brush. He wore his tie tucked into his shirt and his trousers were always up round his chest, his belt too tightly drawn.

We drove downtown to The Pen. It was familiar, that drive up bustling Nathan Road, around into Salisbury Road with that fabulous view of the harbour, a junk bobbing offshore like some picture postcard. Then we swung into the front driveway of The Pen, jostling with Rolls Royces for a spot.

The front door was flanked by large stone lions and bellhops with white hats and gloves smiled and swung the doors open wide as we went into and walked though the lobby to the doctor’s rooms upstairs.

The Peninsula was like a one stop shop for us. My parent’s accountant and lawyer had rooms there and there were all sorts of offices as well as guest rooms above and beyond the lobby. Our barbershop was in the shopping arcade along one side of the foyer. I was glad we had moved barbers to the Pen because when we first came to Hong Kong my father used to take us to a Chinese barber in Mongkok who gave us bowl cuts until and smothered us in Bay Rum until our protests forced a change.

Our Scottish medico, Dr Wylie was on the first floor. Upstairs, in his rooms, he unwrapped my bloodied bandages, looked at my fingers and then guided my hand towards a jar containing some foul smelling antiseptic of some sort.

“This will sting a bit,” he said. My mother watched on, applying some powder from her compact as she did so. We were at The Pen, after all. Certain standards of appearance had to be met.

Afters soaking my fingers in the yellow solution for ten or fifteen minutes I was allowed to remove them and Dr Wylie, wearing his white coat as proof that he was, indeed, a professional, looked my fingers over, declared that I was going to lose two fingernails but that there had been no other damage.

My mother and I went outside then and she attended to the bill. The girl at the counter wore a nurse’s uniform but whether that was just for show or nor I wasn’t sure.

We came to these rooms occasionally, mostly to get our shots.

In the 1960s there was still cholera in Hong Kong and various other contagions that struck fear into the hearts of gwai los. We were constantly being injected with a new vaccine against some unspeakable Oriental horror. As kids we often felt like human pin cushions but it was all to protect us from the dangers that lurked alongside our colonial idyll, spreading occasionally from what my parents occasionally referred to as “the Chinese areas”. Which was most of Hong Kong really.

After the doctor we went downstairs to the lobby where, on account of my injury, I was allowed to order a Coke float, Coca-Cola with a scoop of ice cream, a treat usually reserved for Saturday morning visits. My mother ordered coffee which was served in an immaculate bone china cup. She sipped at that while I slurped at my coke.

It was busy in the lobby, it always was and after a while my father found us. His office was just round the corner in downtown Tsim Sha Tsui but much of the serious business of his construction company was done at tables in the lobby of The Pen, in the gilt rococo splendour. And as I said, he felt at home there. Maybe too much so.

My father joined us for a few minutes but soon went back to a table nearby where he was having a meeting with two rather smooth looking Europeans and one of his Chinese employees who was not appropriately dressed for The Pen wearing black slacks and a cheap white shirt (you could see his string singlet underneath) with a pen in the top pocket while the Europeans were in sharp suits with tie pins that glittered when they moved.

Dad looked so at home here because the hotel had been part of his life for so long beginning in those pre-World War Two years when Hong Kong was little more than an exotic outpost.

In the post war years The Pen was yet again the centre of the Brown family’s social life. My father’s family lived, like us, at Kowloon Tong and The Pen was where they met and partied. An old menu in dad’s rugby album has always served as a reminder of those gracious bygone days. The menu, for the Hong Kong Football Club’s annual dinner dance at The Pen included such delicacies as clear turtle soup, fried garoupa and charlotte russe for dessert.

When we moved to Hong Kong in 1963 there were people sitting at tables in the lobby at The Pen who had been sitting at those same tables since the 1940s. Presumably they occasionally went home.

The lobby was frequented by British civil servants, businessmen, spies (according to my father) who were keeping an eye on China, journalists (China watchers such as the famous Australian scribe Richard Hughes) and many who others who, like my father, regarded the lobby as their lounge room or office. Ted Brown was friendly with many of the lobby legends, including Jock Prosser-Inglis who always occupied the same table and Fred Clemo who ran his travel agency from the lobby. He had offices elsewhere in the hotel but did most of his serious business from a table in the lobby that he often shared with Inglis.

There were often famous faces at the tables too and the guest list at The Pen over the years has been an impressive one with a cavalcade of movie stars and royalty.

Sometimes, my dad, never backwards about coming forward, would spot a famous face, make himself known to them and would turn up at home later with autographs on drink coasters.

One day he spotted the American actor Steve McQueen having a drink in the lobby with film director Robert Wise. McQueen was a Hollywood god in the 1960s and was in Hong Kong shooting the film The Sand Pebbles, which came out in 1966. It was a drama set in China in 1926 when the fictional gunboat USS San Pablo patrolled the Yangtze River during clashes between Chiang Kai-Shek’s troops and Chinese warlords. McQueen starred as machinist’s mate 1st class Jake Holman.

This being the Cold War and all, filming in China was not really an option so the waters off Hong Kong had to serve as the Yangtze and presumably McQueen and wise were staying at The Pen while on location.

My father had simply sat down at their table at The Pen, introduced himself to the pair and enjoyed a whisky with them, obtaining their autographs as a trophy and proof of a brush with fame which turned out to be just one of many.

My mother was miffed that she hadn’t been there to meet McQueen too.

There was always a genteel hubbub in the lobby punctuated occasionally by what always sounded to me like a bicycle bell but was, in fact, the smartly dressed bellhops moving through the crowd with small blackboards held aloft.

The bells were attached to the handles of these blackboards and as they walked through the lobby the bellhops would ring the bells to draw attention to the names emblazoned on the slates. This was the way one learned that one had a telephone call waiting.

The sound of the bell ringing punctuated any sitting in the lobby at The Pen. My father insisted that half the calls were fake – that businessmen paid the staff to page them so they looked important in front of their colleagues and clients.

Service was always at a premium at The Pen. In fact you couldn’t get way from the service, even if you wanted to, not even in the loo.

It always made me feel a little uncomfortable, going to the men’s room, because there was always an attendant in there, smiling and greeting you when you went in although really, you just wanted privacy and to attend to your business.

The attendants was there to hand you cold scented towels at the end of your visit. If you had change in your pocket you might leave a tip on the small silver tray that sat on the stool nearby.

In the loo at The Pen it was always an older man in a starched white jacket and black pyjama pants which was better than the toothless old ladies that attended some men’s loos in Hong Kong in those days. It’s hard to pee when you’re being grinned at by a Chinese granny with no teeth.

Being at The Pen after my doctor’s appointment was special because mostly we would only get to visit on a Saturday morning after ten pin bowling. We were in the Little League at a nearby bowling alley in Middle Road. That street ran behind The Peninsula and separated the hotel from The Peninsula Court, a sort of annexe for more permanent stays which was a residence for some old Hong Kong hands and those who wanted an extended stay. The writer James Clavell, author of Noble House and Taipan lived there with his wife and children for a year and a half in the early 1960s.

If we weren’t ten pin bowling on Saturday morning we would be next door to The Pen at the YMCA which had a prime harboutfront position next door to the swankiest hotel in town. The Y also had rooms where Europeans stayed but snobbishly, we tended to look down on anyone who was billeted there. They must be poor, we concluded.

We went to The YMCA for gymnastics, to play ping pong and engage in other organised fun and to swim in what we thought must have been the most highly chlorinated swimming pool in the world. The water was actually white and the smell of chlorine assaulted your senses as soon as you entered the vast indoor chamber where it was located. We surmised that the chlorine was to counter the urine and local diseases that lurked beneath the surface so we put up with it.

After our Saturday mornings at the Y, my sister and I would toddle across the road to The Pen to meet my mother and younger brother and sometimes my father. We would have our Coke floats and wait for my dad who was often visiting one of his construction sites. Very occasionally I would go with him although I could never understand how such a mess could eventually turn into a building.

After The Pen we might go to the Kowloon Cricket Club for lunch or just back to Kowloon Tong. As kids we didn’t eat much at The Pen but my, mother and father often went to the glamorous Gaddis, a French restaurant that was one of the places to be seen in Hong Kong in the 1960s.

Just the name Gaddis conjured up glamour and the high life. Such heady places were off limits but that heavenly lobby was a family affair at times because The Pen was the place to meet. And apparently the place to be rushed to with a suspected broken finger that turned out not to be broken after all.

Sitting in the lobby, sipping my Coke float, my finger still throbbed but I was distracted by the sweetness of the drink and I enjoyed sitting there watching the people coming and going, wondering why some rich Chinese women insisted on wearing fur coats in a subtropical climate.

I watched dad, back at the table with his business associates, smiling and being rather expansive about something while my mother attended to her make-up again. Soon she waved down the bell captain and asked him to call for our driver, if he wouldn’t mind, so that he could bring the car around front.

Bellhops pulled the huge glass front doors open, their white gloves gripping the impressive brass doorhandles. We passed by the stone lion sentinels, baulked at the heat and humidity and then slid into the interior of the Jag and we were away.

I would, my mother explained, not be going back to school that day so I sat back with some satisfaction and watched the crowds jostling on the busy footpaths of Nathan Road as we glided towards Kowloon Tong.

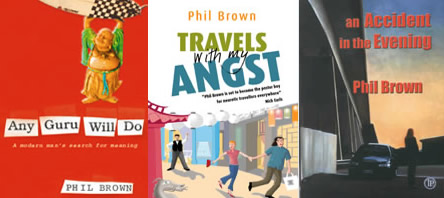

by Phil Brown

Copyright © Phil Brown