BRUCE LEE LIVED HERE

Short Story by Phil Brown

It wasn’t exactly the Garden of Eden. We stood on a path in Kent Road Garden in Kowloon Tong surveying this pocket handkerchief remnant of the past, a small patch of colonial order in modern Hong Kong where the past has been so often erased in pursuit of the future.

My son Hamish looked around unimpressed, as the sweat beaded on our brows, as if to suggest it was hardly worth the trek from downtown Tsim Sha Tsui where we were staying in the cool confines of the Sheraton Hong Kong.

“Bruce Lee lived here,” I said trying to make it sound more interesting that it probably was. “Well, he lived a few streets south, actually.” The Kung Fu star had moved to Kowloon Tong, a sedate suburb known for its grand residences, in 1971, just over a year after we left Hong Kong to move back to Australia.

His house, Crane’s Nest, was in Cumberland Road not that far from where we stood. We lived a street over from Kent Road. All the streets around here have English names and they still have them today which seems anachronistic but heartening. Bruce Lee died in the house in Cumberland Road in 1973, apparently of a bad reaction to some medicine he had taken although I prefer the conspiracy theory. It goes kind of like this: Chinese martial arts masters actually had him assassinated for revealing the secrets of their inscrutable mystical arts to the west. That theory concludes that he was killed using the ancient technique of dim mak which involves a deadly touch by a master, one that sets up vibrations in the body so powerful they can kill someone. Cool.

Bruce Lee’s house eventually became, for a while, one of the many ‘love motels’ that proliferated in Kowloon Tong at one stage. By ‘love motel’ I mean knocking shop. There aren’t as many of those ‘love hotels’ now but they are still there. Around Devon Road and the immediately surrounding streets you’re more likely to find schools, kindergartens, and the headquarters for a number of Christian churches alongside vast mansions owned by the super-rich who come and go through electronic gates in limousines with darkened windows that allow them to remain unseen.

You can see the backs of some of these mansions standing in Kent Road Garden which was a stifling experience on this June day.

“You must be shapeless, formless, like water,” I said looking around. “When you pour water in a cup, it becomes the cup. When you pour water in a bottle, it becomes the bottle. When you pour water in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can drip and it can crash. Become like water my friend.”

“What?” Sandra asked. “What the hell are you talking about?”

“That’s Bruce Lee,” I said. “From Enter The Dragon.” Hamish smiled knowingly because we had watched that Bruce Lee classic recently.

Rather than standing sweating in this little colonial park we would have actually been far more comfortable in the nearby mega-mall, Festival Walk, which is probably the main reason most people come to Kowloon Tong which is not exactly on the tourist map.

Festival Walk is a vast, sprawling retail paradise. The air-conditioning is Arctic in the Hong Kong manner … so chilly, in fact, that they have an ice rink in there. You can travel to Festival Walk and back on the MTR from Tsim Sha Tsui without ever seeing the light of day or feeling the heat of the day, an attractive proposition in the steamier months. It gets so humid at times in Hong Kong I recall water used to form on the walls inside our home in Kowloon Tong in the days before the whole world was air-conditioned. We did have boxy old air cons for our bedrooms in those days but the rest of the house was cooled by fans.

One thing’s certain - it would be a lot cooler in Festival Walk than it was in Kent Road Garden late on a June morning with, according to the weather forecast, a typhoon brewing.

We had come by MTR on one of my far too regular forays into my Hong Kong past, forays my family has become used to, sometimes reluctantly. But not always.

It guess it might have been hard for them to get a take on what made Kent Road Garden so special to me. It’s quiet spot in a bustling city, a little bit of Kowloon that has steadfastly remained the same in an urban landscape that is changing so fast that it takes a certain imaginative spirit to find remnants of the past that can evoke bygone days.

We strolled up and down the well-ordered path, admired the topiary and took note of the graffiti-like scrawl on the wall nearby that said COMMUNIST. That seemed apt and it sparked memories of my boyhood days when Communism was feared and loathed. The years we lived in Kowloon Tong were years when the Cultural Revolution was in full swing and Hong Kong was an enclave attached to China, a country where chaos reigned.

The Vietnam War was raging in Indo-China and the Cold War seemed very real. Hong Kong was a garrison town under threat. The Red Guards had sparked riots and Chines communist militia had made incursions across the border. A Gurkha battalion was brought in to secure the colony.

While we lived in a colonial idyll on the one hand there was a sense that the Communist threat loomed large.

Looking down from Kent Road Garden I could see the railway line, still there. In the 1960s that line was a reminder of the Red Peril because that line went all the way to

Canton, which was a forbidden city in the terrifying land beyond the border.

People who went to China on that train sometimes never returned according to my father. He had lost several employees who had gone to China to visit family and were never heard from again. Working for a construction company owned by a capitalist paper tiger like my dad wouldn’t have been acceptable to the rabid Red Guards. We regarded them in the same way people might regard the fanatics of ISIS now and we had seen them on the streets of Kowloon, local cadres demonstrating, shouting, their faces twisted in hate, waving their little red books of Mao’s quotations at the police who put down their riots.

The railway line was so close to the Kent Road Garden and it looked so peaceful. When the train ran by it seemed harmless enough. Sometimes we scrambled down there and lingered by the line, sometimes putting our ears to it (if it wasn’t too hot) to try to gauge if the train was coming.

When it did rattle by, as a kind of gesture of protest we would gather stones and throw them at the train. I stood in the Kent Road Garden telling Sandra and Hamish this story when I realised that what I was describing was the sort of vandalism that would appal me if I heard my own son had been engaged such errant behaviour. But somehow we felt it was entirely acceptable because we were the colonial masters in this place and chucking stones at the train was an acceptable way of railing against the communist menace. And there it was writ large in graffiti on the wall nearby …COMMUNIST. The rest of the message had been obscured.

I wondered whether Bruce Lee had ever lingered on a path here in the Kent Road Garden. Maybe he did some Kung Fu moves under the trees in the cool of a Kowloon Tong the evening. Whether Lee practised his moves here or not, I know others certainly did. Each morning and afternoon the Kent Road Garden was a favourite gathering place for locals who gathered and practised their Tai Chi routines here. Tai Chi was one of those inscrutable oriental things beyond the ken of us colonial kids. We were mystified by these people who would turn up in the gardens in their pyjamas, slowly moving like so many praying mantis, grasping invisible birds’ tails with their outstretched hands. They seemed lost in a mystical world beyond this one, which we should have respected. But instead we would hide behind the nearby bushes and taunt them and we were always amazed that they remained unperturbed and just kept slowly going through the motions as if we weren’t even there.

We eventually graduated to throwing little twigs at them in a desperate attempt to break their trances but they just kept on waving their arms like slothful human windmills and in the end, each time, we would give up the ghost and move on top some other misbehaviour.

Every afternoon after school I would get home, don my blue and white rubber-soled sneakers and go out to play and make trouble in one of the several parks in the area, often Cornwall Road Park which was around the corner from our house. There was a small shop in the corner of the park on Cornwall Road and it was run by a local Chinese family who lived in a nearby squatter’s area. In those days there wasn’t enough public housing to hold all the refugees who flooded into Hong Kong to escape the communists. This family often left their grandma to look after the store which was a mistake which we ruthlessly exploited. We would go in there in a small group and while one kept her busy the others would pinch lollies from the shelves and stuff them into pockets before running off.

We played cricket and softball in the park on Cornwall Road. Kent Road Garden wasn’t big enough for that sort of thing but it was on our beat and one of the reasons we went there was to spy on the Chinese schoolgirls who congregated there in the afternoon. There was a little shop in the park selling drinks and ice blocks, popsies we called them then, in the English manner. We would grab a popsy or a bottle of Coke or Green Spot, the favourite orange soft drink and linger there watching as gaggles of girls, in their cute little sailor uniforms, sipped their soy milk nearby. The thought of that made us gag. I had tried soy milk once and the taste was so foreign I spat it out immediately. It was a Chinese drink, we decided, not for us.

I often came here to watch those girls with my Spanish American friend whose name was, rather appropriately, Randy. I’m not telling talks out of school by telling you that he was a dirty little bugger. As 11 year-olds we were developing an interest in girls although I was unsure how it all worked. I had seen some photos in a pornographic magazine a Pakistani friend had brought to school one day and was revolted by that. I had furtively scanned my father’s Playboy magazine’s when my parents were out but that was the extent of my sex education.

To me it wasn’t really about sex. These Chinese girls seemed exotic and ethereal to me. We would sit on a bench and watch them, quite blatantly, as we sipped our dinks or lurk under a tree or behind the topiary and sometimes they would notice us and giggle and say things behind their hands. Randy occasionally made rude gestures towards them, much to my horror.

To me they seemed almost courtly, like the mother of pearl figures on a lacquer screen that was displayed in our living room. A poem I wrote many years later, The Chinese Princess, was inspired by my memory of lurking in Kent Road Garden, watching those school girls.

On the day of our family pilgrimage we were the only people in the Kent Road Garden which was so much smaller than I recalled it. But at least it was still there. But it was too humid to linger for long. I suggested, to mild protests from Sandra and Hamish, who yearned for some air-con, that we might walk past our old family home at 7 Devon Road. I have made visits here on and off since my first trip back to Hong Kong in 1985 and have peered through the gap in the big iron gates to satisfy myself that it was still there. Somehow that comforted me.

So we left Kent Road Garden and I led Sandra and Hamish up to Cornwall Road and then around into Devon Road. From Cornwall it’s only around 50 metres or so to our old house but when we go to the appointed spot I was confused. The front wall and gate was no longer there. I could discern where the house next door had been. An American family had lived there, the father something big in Pan Am. They had a tennis court and were very sporty and once brought us a real Christmas tree back from Japan. Their house wasn’t there any more having been replaced by a vast Italianate mansion with a Bentley in the driveway. Where the iron gates that had marked the entrance to our driveway once were there was now hoarding. I found a gap and peered through, the sweat on my brow dripping onto my glasses.

What I saw shocked me. The house was gone. It was just a building site where they were probably erecting a vast monstrosity like the one next door.

“It’s not there,” I said as I leant back and scratched my head. ”Can you believe that? They’ve knocked it down.”

It seemed like sacrilege. It was a substantial structure that must have taken some work to get rid of but they had, indeed got rid of it. “Shit,” I said.

I was devastated because that house was a symbol for me of everything grand and wonderful about our years in Hong Kong. It was like a little palace or a diplomatic compound with its high walls and its block of servants’ quarters out back. In a time of uncertainty it was the one constant. We felt safe there even at the peak of the riots in 1967 when the Cultural Revolution spilled onto the streets of Kowloon. There was a curfew at that time and our house was a safe place in a world gone mad.

On earlier visits I noted that they had added to it, built into the big front garden. At one stage a publishing house was based there and though I couldn’t see the familiar faced any more I knew that the essence of the house was probably somewhere in that new complex.

It couldn’t have stayed as it was on that big block that spread between the road and the laneway that ran behind most of the blocks in Kowloon Tong. The land was too valuable.

And now some tycoon was building his own palazzo on this scared site. Rightly or wrongly I consider that place my happiest home. Our sudden departure from Hong Kong in late 1969 robbed me of life there but I have internalised that house and I walk through nit in my dreams and now that is the only place it still exists.

We walked away then down Devon Road and around the corner back towards Kowloon Tong station. I decided I wanted to catch a taxi back downtown and there was a rank outside so we jumped into a taxi and sighed with relief because the interior was suitably frigid.

“Tim Sha Tsui,” I said to the driver and he just looked at me. “Tsim Sha Tsui. Downtown … Sheraton Hotel, ok?”

He shook his head to signify he hadn’t a clue what I was stalking about. Either that or he was pretending not to have a clue what I was stalking about. It was hard to know which.

“Right,” I said flinging the door open. Sandra and Hamish followed, flustered. “Let’s try this one,” I said but I opened the door first and said to the driver, as a kind of question …

”Tsim Sha Tsui?” he shook his head. It was hot as Hades and I was determined to have a nice cool cab ride back to the Sheraton.

“One more,” I said and I opened the door of the third taxi at the rank. A few amused passers-by had stopped to watch the flustered gwai lo.

“Tsim Sha Tsui? Sheraton Hotel?” I said and he nodded.

We flung ourselves into the cab and he sped off and soon we were driving downtown on Waterloo Road. I sat back and pictured our house, framed by jacarandas, fringed with bamboo with those big, blue, iron gates and the compound wall that kept the world at bay and made our little colonial enclave safe.

“I can’t believe it’s gone,” I said.

“At least Kent Road Garden is still there,” Sandra said.

“Yes,” I said wearily. “I guess that’s something.”

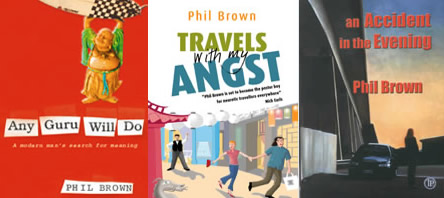

by Phil Brown